Top-Two Thompson Sampling: Theoretical Properties and Application

Top-Two Thompson Sampling: Theoretical Properties and Application

Highlights

- The algorithm has several desirable theoretical properties, especially for practitioners who assume reward distributions of arms/interventions to be Bernoulli or Gaussian.

- A simulation based on a recent intervention tournament suggests a far superior performance of the Top-Two Thompson Sampling algorithm compared to both Thompson Sampling and Uniform Randomization in terms of accuracy in the best-arm identification and the minimum number of measurements required to reach a certain confidence level.

- Implementation: Colab Notebook

Motivation

Whether in academia or industry, experimenters face the challenge of identifying the most effective treatment/intervention/design. This post provides an overview of the Top-Two Thompson Sampling (“TTTS”), an intuitive variant of Thompson Sampling for the best-arm identification problem where the objective is to find an optimal design to maximize the total reward over a series of trials. In particular, we delve into its theoretical properties and implement it on intervention tournament data from the Strengthening Democracy Challenge.

Top-Two Thompson Sampling

Thompson Sampling is a Bayesian algorithm that balances the explore-exploit tradeoff: “exploiting what is known to maximize immediate performance and investing to accumulate new information that may improve future performance.”(Russo et al. 2020) This heuristic proceeds in three steps: (1) initialization of reward distribution parameters of each arm with flat/uniform priors, (2) selection of which arm to “pull” based on randomly sampled values from each arm’s reward distribution, and (3) update of the selected arm’s reward distribution parameters based on the reward observed. One advantage of the algorithm is that while arms with higher expected rewards are more likely to be selected, there is a chance that actions with lower expected rewards could be chosen.

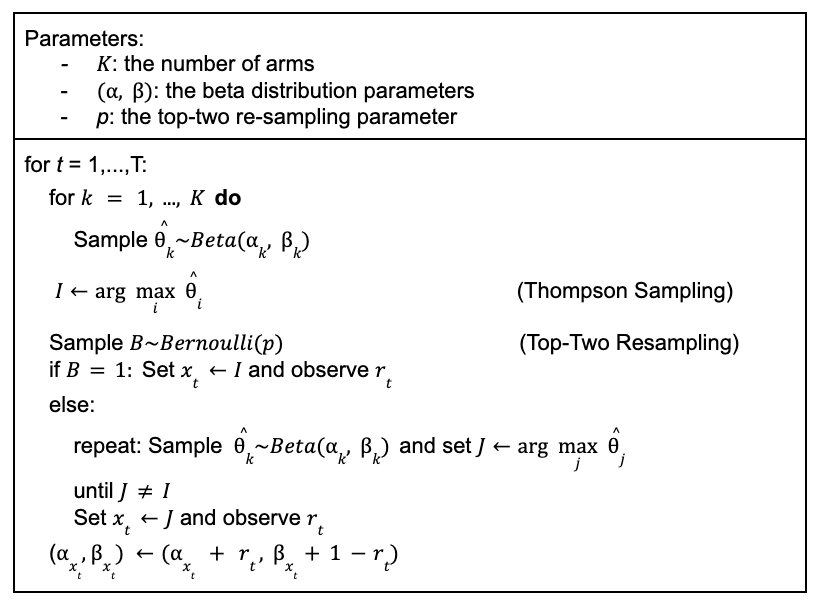

Despite its intuitive appeal, there are practical issues with the algorithm, chief among them being large measurements required to reach a high level of confidence in identifying the best arm: its objective of maximizing the rewards leads it to allocate “almost all effort to measuring the estimated-best design and requires a huge number of total measurements to certify that none of the alternative designs offer better performance.”(Russo 2020, p. 1626) TTTS overcomes this issue by adding the re-sampling step to the original algorithm, which effectively increases the exploration. More concretely, the algorithm compares the top two arms with the highest sampled values and makes a decision based on a coin flip (i.e., a draw from a Bernoulli distribution with probability p). Below is the TTTS algorithm applied to the Bernoulli Bandit where there are K arms and each action yields either a success or a failure.

Theoretical Properties (Russo 2020)

Before diving into the implementation, we provide high-level theoretical properties of the algorithm. More interested readers should check out the original paper.

- Key Assumptions:

- A frequentist setting where the true quality of each arm is fixed.

- The reward distribution for each arm is a member of a parametric family (i.e., the true reward distribution is parametrized by a certain unknown parameter).

- Boundedness assumptions (i.e., priors only defined over a compact set), ruling out cases such as multivariate Gaussian priors.

- Asymptotic optimality with tuning: algorithms achieve the exponential rate of posterior convergence, where the posterior probability assigned to the event that some design other than the true best design is optimal converges to zero as measurements are collected.1 One thing to note is that the theoretical guarantees for fixed-confidence best-arm identification have only been obtained when the arms are Gaussian with known variances (Jourdan et al. 2022).

- Robust results for a simple version of the algorithm with unbiased coin: the exponent attained with p = 1/2 is within factor 2 of that attained under the optimal tuning parameter.

- NOT a “fixed-budget” setting where the objective is to minimize the probability of making an incorrect decision after a given budget of measurements is depleted. Rather, the algorithm achieves asymptotically optimal guarantees in the “fixed-confidence” setting where the objective is to minimize the expected number of collected samples while guaranteeing that the probability of making an incorrect decision after the stopping time is less than a pre-specified level (Qin 2022).2

On point #2, the generalizability of the guarantees should not be a significant problem for most applications that assume Bernoulli or Gaussian arms. The complexity of tuning the re-sampling parameter (p in this post, β in the original paper) does not seem to pose a significant challenge either as point #3 suggests the reasonable guarantees for simply setting p = 0.5. Point #4 is rather unfortunate, especially for academic researchers with budget constraints. Nevertheless, the recent work that proposes a Bayesian elimination algorithm with theoretical guarantees in the fixed-budget setting suggests a comparable performance between the authors’ algorithm and TTTS (Atsidakou et al. 2023), so the latter still might be a good choice for budget-constrained practitioners.

Simulation: Strengthening Democracy Challenge (“SDC”)

We apply the algorithms to the SDC, a recent intervention tournament that was designed to reduce partisan animosity. The actual tournament itself garnered 25 different interventions, and each intervention was allotted about 1,000 respondents. In the given context of best-arm identification, we address whether the proposed TTTS algorithm can outperform the Uniform Randomization (“UR”) and Thompson Sampling (“TS”) in correctly and efficiently identifying the best intervention. For the purpose of this post, the main outcome of partisan animosity, measured in a 0-100 thermometer rating of the other party members, is transformed to be binary with an arbitrary threshold of 40: if a given partisan responded with the rating of the other partisans above 40, the transformed outcome takes the value of 1, 0 otherwise.3

To fully leverage a large number of interventions, we construct three different scenarios with ten interventions in each to gauge algorithms’ performance in such situations with the true best intervention in the parentheses with “success” rates of all arms included in the scenario:

- Clear Winner: there is a single intervention that clearly outperforms other interventions (True Best Arm = Treat1; [0.57, 0.43, 0.43, 0.42, 0.43, 0.41, 0.42, 0.41, 0.40, 0.43]).

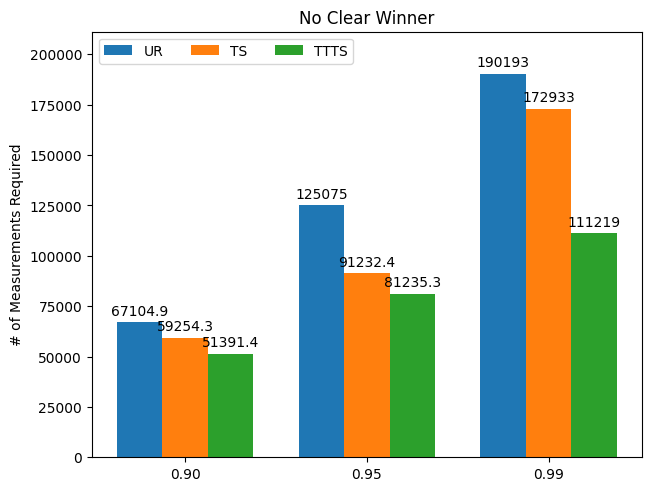

- No Clear Winner: there is no single intervention that clearly outperforms other interventions (True Best Arm = Treat10; [0.43, 0.43, 0.42, 0.43, 0.41, 0.42, 0.41, 0.40, 0.43, 0.44]).

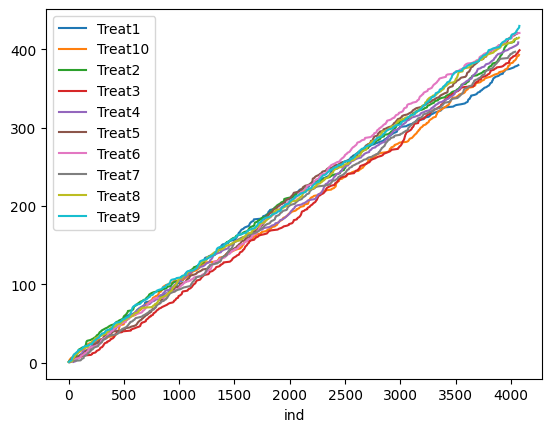

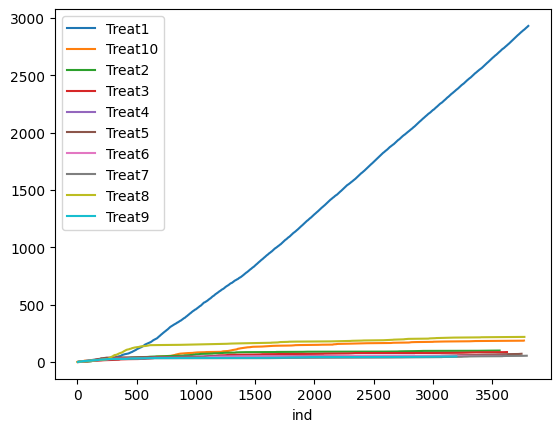

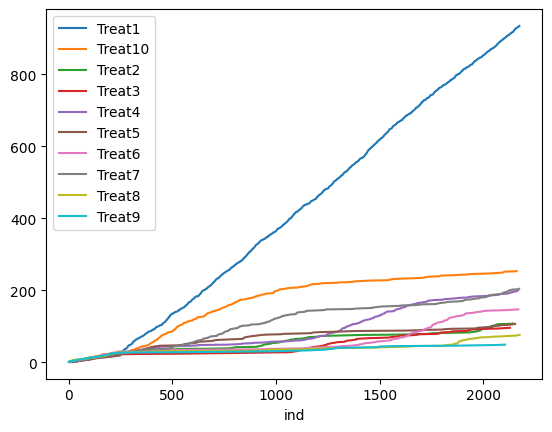

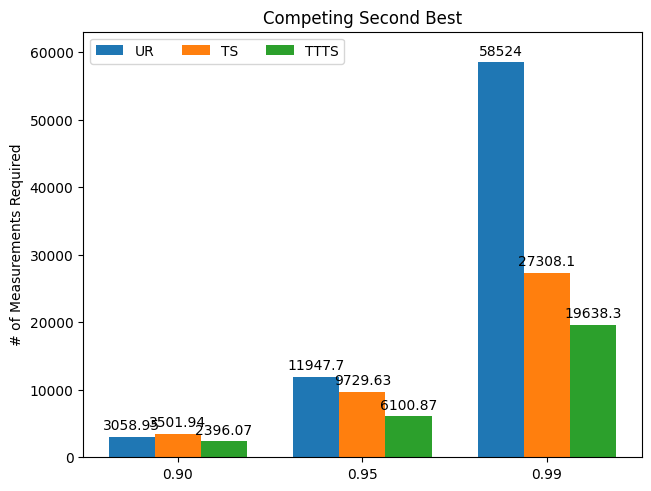

- Competing Second-Best: there are two competing interventions that clearly outperform other interventions. (True Best Arm = Treat2; [0.53, 0.54, 0.43, 0.43, 0.42, 0.43, 0.41, 0.42, 0.41, 0.40]). We repeat the simulation 100 times for each algorithm and scenario. The figures below show the treatment assignment over time for a single simulation in the “Clear Winner” scenario. UR assigns about an equal number of measurements to each treatment, whereas both TS and TTTS algorithms quickly identify the true best arm (Treat1) and assign more measurements to it. See the accompanying Colab Notebook for the implementation codes.

| UR | TS | TTTS |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Result 1: Correct Best-Arm Identification

The first outcome of interest is the accuracy in identifying the best intervention. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all three algorithms perform well when there is a clear winner, and the difference becomes more meaningful when there is a competing best arm. The table below shows the results by algorithms and the scenario types:

| Algorithm | Scenario Type | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Uniform Randomization | Clear Winner | 0.99 |

| No Clear Winner | 0.92 | |

| Competing Second-Best | 0.82 | |

| Thompson Sampling | Clear Winner | 1.0 |

| No Clear Winner | 0.99 | |

| Competing Second-Best | 0.92 | |

| Top-Two Thompson Sampling | Clear Winner | 1.0 |

| No Clear Winner | 1.0 | |

| Competing Second-Best | 0.92 |

Result 2: Number of Measurements Required to Reach Given Confidence Level

Now we consider the “efficiency,” as in how many measurements each algorithm needs to reach a given level of confidence in ascertaining the best arm. For example, a confidence level of 0.9 means the algorithm has assigned 0.9 probability of being best to the best-performing intervention. These probabilities are estimated via Monte Carlo simulations. In all scenarios, we clearly see that TTTS outperforms the other two algorithms: it requires far fewer measurements to determine the best arm with a high degree of confidence.

| Clear Winner | No Clear Winner | Competing Second-Best |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Takeaways

- For simple Bernoulli or Gaussian Bandit problems, TTTS could be a compelling choice for best-arm identification.

- UR likely works just as well as TTTS for lower levels of confidence, but for those requiring higher levels, TTTS should be a sensible choice.

- The best-arm identification problem in the fixed-budget setting is an active area of research, and the recent evidence suggests good performance by TTTS that does not have theoretical guarantees in such settings.

-

This post omits the discussion of the tuning of this re-sampling parameter. As the author denotes, the tuning process is complex, “spoiling some of the elegance of the top-two sampling algorithms.”(Russo 2020, p. 1637) ↩

-

For an example of a recent effort in further identifying asymptotic guarantees for the fixed-budget setting, see (Atsidakou et al. (2023)’s) [https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.08572] recent work on a Bayesian elimination algorithm. Their simulations suggest comparable results for their elimination algorithm and the TTTS algorithm, the latter of which does not have the theoretical guarantee in the fixed-budget setting. ↩

-

Such selection of threshold is completely arbitrary, and the transformation was done to construct a Bernoulli bandit problem. ↩

Comments